Even a seemingly blank space has points and lines of emphasis that create a physiological and psychological response that we are rarely consciously aware of, either while standing in a space ourselves or felt while observing others in a space. This emphasis shifts as other bodies and objects are added to the space forming spatial relations between them. Also more significantly thresholds can be easily created with just the addition of two objects to the space. All of this does not require complex architecture. This spatial awareness was explored in workshops by Clive Barker (Theatre Games 1977) as it is regularly exploited in performance. I experienced Barker’s workshops and have found an awareness of the spatial effects useful in approaching both the study of ritual and in the performance of rituals. Thomas A Markus (Buildings and Power 1993) observed that for buildings their raison d’être is to interface Visitors and Inhabitants and to exclude Strangers. The relations between these three groups are expressed through the use of the thresholds and spatial emphasis.

This page is developed from a paper given at the BASR (British Association for the Study of Religions) 2014 Conference at the Open University, Milton Keynes, UK.

On this webpage I will explore three types of space:-

- Body Space. The space of and around our bodies that we most frequently experience as ‘our personal space’.

- Built Space. This does not refer to the architecture, but the space that is created within it. We inhabit the space, not the walls. It has lines of emphasis that are used at sometimes and avoided at others.

- Conceptual Space. These are the spatial metaphors we live by and most importantly the ‘Container’ image schema observed by Lakoff and Johnson (1980 and 1999).

These three are closely linked and when they cohere the effect is powerful.

Body Space: awareness and state of mind

The first part of this section is mostly based on the particular workshops I experienced during my Theatre Studies degree at Warwick University in the mid-1980s. These were taken by Clive Barker (1931-2005) the professional actor, director, drama teacher and lecturer, who was a member of Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop in its heyday in the mid-1950s. He made many observations and experimented with techniques to improve actors training. These mostly involved working with children’s games as the primal unself-conscious form of theatre, to get actors to move naturally. Though play and theatre overlap with ritual, it is his work on the fundamental qualities of space and bodies moving through it that I will be drawing on. Most of the ideas I shall be explaining here are considered in his book Theatre Games (Barker 1977: pp. 135-155). His practical approach and the drama workshop origin of his observations lends itself well to demonstration, but not so well to description as it is an embodied experience. The illustrations that follow show the positions and movements, but from the outside and not the feel of the experience of space. These really require physical performance to provide the full embodied experience. If you do not have a strong spatial sense imagining the effects of the following exercises will be difficult.

The following exercises I have run in a workshop setting in an open unfurnished hall. To begin with participants need to have their conscious awareness of their unconscious and physical responses raised by the On-Centre Exercise which would take 15-60 minutes to achieve it effects depending on the group. Usually the more experienced ritual practitioners can get ‘on centre’ quicker.

Stand where you have clear space around you for a couple of paces. Close your eyes and listen carefully to all the subtle sounds around you. Focus your hearing on each direction in turn to find what is there. Or focus on particular sounds and pick out which direction they come from. Notice how near or distant the sound is. Notice how directional or how diffuse the sound is (a ticking clock, or the wind howling across the creaking roof).

Now open your eyes. Become aware of the visible aspect of the space between you, and others, and the walls. Now take a step forward. Try and maintain your awareness of the sound space around you. Note the differences of perspective of sound and space as you move. Overtime you will become aware of differences within the space.

During this exercise you will be gradually adopting a more erected posture, with your body balanced on its natural centre of gravity. This is what actors call being ‘on-centre’. Your attention is focused all around you, and not distracted by the direction of your vision, which is what normally occurs. This exercise is a means to become aware of the three dimensional space that is surrounding the body. Your personal space with you at the centre, a sphere of your bodies reach, touch and movement. This sphere about the body is what the dance teacher Rudolf Laban called the ‘Kinesphere’. When you are ‘on-centre’ movement is much easier to make. With this exercise the challenge is to maintain this awareness with the eyes open, and whilst moving. This awareness is necessary for the rest of the exercises, described later.

This spatial awareness is a very natural one, but it lies deep within the sub-conscious, below the conscious seamless picture we create of the world that feels like a detached view from within our skulls. Helen Briggs reported on the BBC website in 2008 that research at Harvard Medical School (published in Current Biology) has studied a man who was rendered blind by a stroke, yet he was still able to negotiate a route around boxes and chairs without bumping in to any of them. Yet as far as he was concerned he was walking in a straight line.

“The patient, known only as TN, was left blind after damage to the visual (striate) cortex in both hemispheres of the brain following consecutive strokes. His eyes are normal but his brain cannot process the information they send in, rendering him totally blind. However, he was previously known to have what is called ‘blindsight’ – the ability to detect things in the environment without being aware of seeing them. For instance, he responds to the facial expressions of others. But he walks like a blind person, using a stick to track obstacles and requiring guidance by others when walking around buildings. A video recording shows him completing the obstacle course set up by the scientists ‘flawlessly’, without the aid of his cane or another person.”

So at a very deep level we are aware of space, and that awareness has deep psychological effects, even when that space is only imagined. The research carried out by Lawrence E. Williams and John A. Bargh of Yale University (summarised by Wray Herbert in 2008 in Scientific American Mind magazine) explored more deeply a known phenomenon that plotting points on graph paper that are close together or far apart induces subtle feelings of being in confinement or wide open spaces respectively. What Williams and Bargh found was those experiencing the closeness were disinclined to want to continue reading extracts from books containing embarrassing or violent scenes. They believe this comes from the deep association of distance to safety. Also it may support the commonly held idea that clutter that fills up your space leads to stress. Even more revealing however when they tested both groups on the strength of their emotional bonds with their hometown and family, was that the group that had plotted points far apart felt more detached or emotionally distant and those plotting points closer felt, well, closer.

“What is remarkable is that this all takes place unconsciously, apart from awareness: the spatial distance between two arbitrary objects (in this case, two mere dots on a graph) is apparently powerful enough to activate an abstract symbol of distance and safety in the brain, which in turn is powerful enough to shape our responses to the world.” (Herbert 2008)

All of this illustrates that space is not just used as a metaphor for relations; it actually shapes them and embodies them, even if the spatial experience is only on paper. Then consider how much more powerful this effect is when combined with all the other senses and emotions of a full religious ritual context.

You can try this yourself. Imagine the feeling of standing at the top of a hill with the wide open sky around you. Stay with that image for a while. Now imagine that you are under a tree there, with rain dripping from it. Notice how your posture and mood both subtly change.

Without any conscious acting your body shifts posture and you feel different. The mind follows the body to such an extent that it can be used therapeutically (Wiseman 2012). For example, something as simple as standing with your hands on your hips, in a superhero style pose, for a few minutes a day has been shown to significantly improve the mood throughout the day.

The psychological effect of space is so fundamental a perception that it pervades language. It can be found in myriad examples of metaphors for states of mind, and emotional relationships. Here are just a few:-

I’m on top of the world, the world is closing in on me, she’s stand-off-ish, he’s distant, we’re meeting halfway, they’re sharing common ground, she stands tall, he crossed me, he slighted me, we are close, she keeps open house, she looks down on people, they brush others aside, they trample over others, they’re coming together, he is broad/narrow minded, she has a big personality, they are open and approachable, she is withdrawn, I can’t get through to him, she takes a stand/position on the issue, he refuses to budge, they don’t know which way to turn, we are lost….

Many of these metaphors relate to the familiar idea of personal space and others interactions with it; that space around you which is regarded as being yours is dynamic, it changes size with setting (just think of the different feeling of being near strangers on the London Underground compared to along a country lane) and with mood. Some equate this personal space with the body’s aura, and some people who dowse claim to be able to detect the edge of the aura, and demonstrate the expansion and contraction of the aura when someone is thinking of happy or sad thoughts. Similarly, Barker describes that on the stage confident actors are said to have ‘presence’. They fill the stage. They are big, and the audience’s attention is drawn to them and doesn’t wander as they move. Actors who don’t have this have no clear sense of their position and their performance is blurred. This ‘presence’ is, according to Barker, difficult to acquire if you don’t have it, but it comes from the actor being strong at the centre of their personal space. Stanislavsky, the originator of method acting called this ‘the circle of concentration’. They stand at the centre of a space defined by their mental attitude. In my opinion the same can be said of experienced ritualists.

Barker rather neatly demonstrated in workshops how the tense of the mind, whether you are thinking of the past, present or future, can be deduced by the body posture and simulated by the actor. He managed to perform the following short scene without any obvious gesturing.

A man is running to catch a train. He arrives on the right platform in time. He thinks about what he heard on the radio news that morning (or something similar). He then realises that he is on the wrong platform. He then hurries off to get to the right platform.

He conveyed the scene without pretending to carry bags, looking at an imaginary watch, or by using any other gestural cues. What he did, apart from running on, standing still and running off again, was altering the subtle orientation of his spine to his head and pelvis. When one is rushing to get somewhere, your head goes slightly ahead of the pelvis. One’s mind is focused on the future. When one has arrived, your head is directly above your pelvis. One’s mind is in the present. When one is remembering something, the pelvis comes slightly before the head. One’s mind is reflecting on the past. This is a sub-conscious reflex that actors attempt to mimic. During rituals it also happens. For ritual acts are also in different tenses; generally speaking; prayers and spells are future/proactive tense, invocation and declaration are present tense, pathworking and visualisation are past/reflective tense. In my experience sometimes the reason for certain ritual acts not feeling right, is that the tense of the pelvis to head relation doesn’t match that of the ritual action. Try doing a spell or invocation while lying down and you’ll see what I mean.

Built Space: emphasis and relations

There is no such thing as an ‘empty’ space. Even within the most neutral rectangular hall where ever you stand you turn the space into place, giving it significance, but the space will enhance or diminish the presence of the body depending on where you stand. And this is without doing anything at all. Just standing there. Actors instinctively spend time getting to know stages that they are unfamiliar with for this reason. Though a strong actors sense of personal space overrides that of a weak actor, the space is the dominant force in the interaction. Barker demonstrated the effect of space in an extended workshop following on from the ‘on-centre’ exercise described above with the Setting Space Exercise.

The requirements for Setting Space Exercises are as for the ‘on-centre’ exercise, with three people to demonstrate in the space (stage) and the observers outside of the space (audience). If time allows several people can have a go at each positioning, and then say what they feel there. If time is short then only one person should try each position. The observers are asked to describe their responses. If the on-centre exercise has worked well then even though they are now outside of the space merely observing, they should still be able to feel their sub-conscious response to the demonstrator’s position. The audience responds to the actor’s position on stage, just as they respond to placing dots on graph paper, or imagining themselves being in a particular space. This Barker calls the ‘kinaesthetic response’.

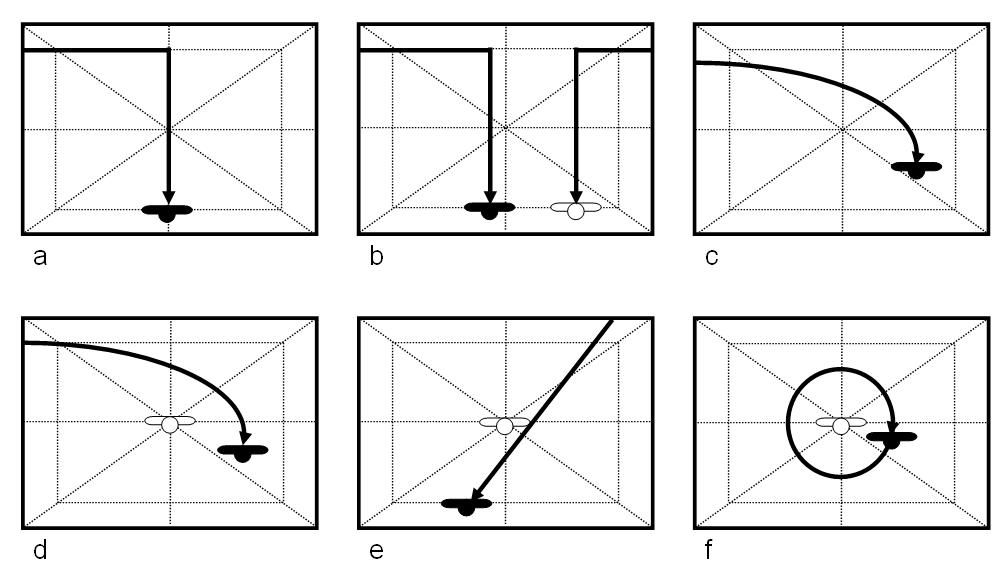

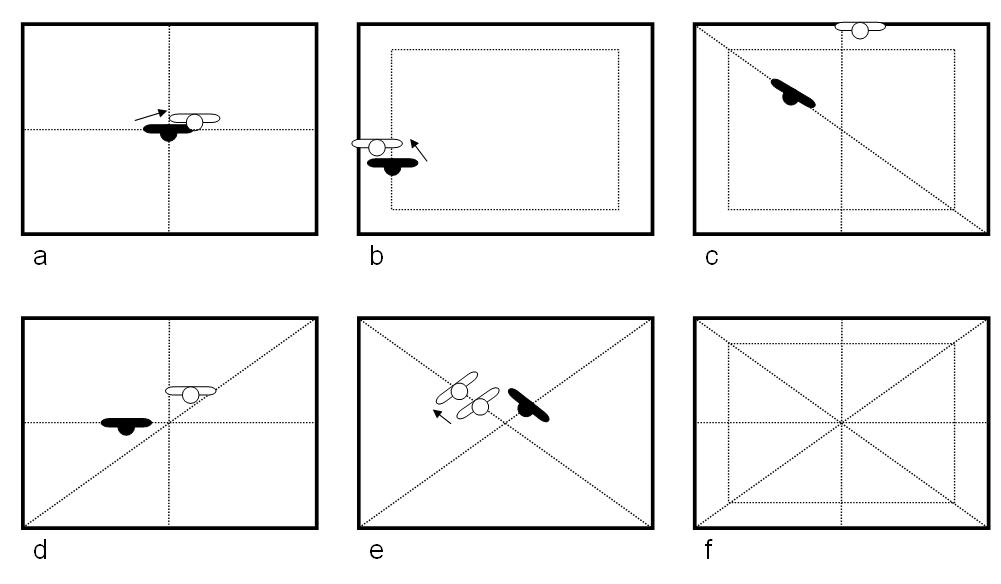

Each of the positionings is illustrate by a diagram showing the space, lines of emphasis within it (dotted), lines of movement (solid arrow), and positions of people (blobs suggesting a view from above of the head and shoulders of a person standing). The people are represented about twice the size for the space illustrated. The observers are outside of the rectangle to the bottom of the diagram, with the demonstrators facing them, as in a conventional theatre. Thirty seconds should be enough time for each position if the group is consciously spatially aware after having done the ‘on-centre’ exercise.

Figure 1. Static positions in space examples.

The first part of this exercise explores static positions in space. In the first two examples 1a and 1b the demonstrator moves from the black to the white position. In 1a the demonstrator is at the absolute centre of the space a very dominant, controlling position, which is diminished a soon as they move off that centre to the white position. This position is difficult to stand in for any length of time, both for demonstrator and observer. In 1b the black position isn’t bad on the edge line, but as soon as they move to even just touch the walls, they merge with it, and are diminished. In the other examples 1c, 1d and 1e there are two demonstrators, one at both the black and the white position. In the later example 1e the white position is moved slightly.

After these positions are felt and responses given by observers and demonstrators, it will become apparent that the rectangular space has lines of emphasis across it. The main ones are shown in diagram 1f above, but there are other parallel lines running at regular intervals. The unit of width when it is apparent is about 0.5m (1.5ft) which is roughly the width of the human body. The body is the perceptual unit of measurement of space. This is also the width of the ‘dead space’ at the edge of the rectangle. A theatre or hall is the optimum size for noticing these lines of emphasis. In an unbounded space, say a large beach, the limits that define the shape of the space are difficult to perceive and so they are not experienced, there is only the space as defined around the body. With spaces of less than seven body widths, such as an average living room (without furniture), the lines will be less well defined as there is less space between them, though the centre, the edge line, and any principle axis will be features of most normal sized rooms.

What also becomes apparent is that without the demonstrators doing anything other than just standing, there are implied status and emotional meanings that observers derive from the positioning of people in space, and in relation to each other. There are very many possible positions and relationships between two bodies in a space. When other people and furniture is added it gets even richer.

Figure 2. Movement in space examples.

The next part of this exercise explores movement in space. In example 2a the demonstrator enters the space at the back turns sharply on to the middle line and then proceeds to the front. Using this centre line of emphasis has the effect of drawing all the attention to the demonstrator. The effect of this is enhanced by opening out the arms wide as progress is made down the centre line. This move is what pantomimes always use for their curtain call, and no matter how bad the show this will always generate a round of applause. It is a very strong expansive entrance, so consequently it is used sparingly. If the demonstrator reverses the move, walking backwards, and bringing the arms in, then it is shown to have an equally rapid diminishing effect. Example 2b is similar. Both routes are weaker as they do not use the centre line, but the white route is better as it uses a lesser line of emphasis which runs parallel to the centre line half way to the edge of the space. Whereas the black route is very much in the shadow of the centre line.

The route used in example 3c ignores all the lines of emphasis. This route does not draw attention to the demonstrator. This sort of curved route can be seen being used by someone scuttling on to sort out something and not wanting to draw attention away from the main action that is going on. Examples 3d and 3e have one demonstrator in the middle while another enters. 3d uses the same route as for 3c, and the black route is totally dominated by the white position. Whereas 3e, though it also ignores the lines of emphasis, the route cuts through the personal space of the white position and then ends on a line of emphasis almost blocking the view of the white position. Though the black position is weaker, it is very challenging. In example 2f black circles white. And though this route does not use any of the lines of main emphasis, it does gain some reflected emphasis by respecting the centre point as well as adding to its importance. However, if the circling is repeated, or if more than one person is involved in the circling, then the emphasis increases. The movement, or the number of bodies, can create an emphasis that is greater than that of the space; just as furniture and architecture shape the space. But obviously a person sized piece of furniture has less effect than a person. Though a hat stand with a coat and hat on it has some presence, and this can be enhanced by it being referred to as if it were a person.

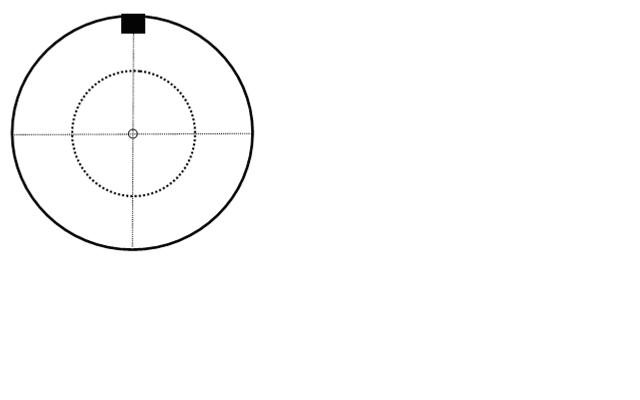

Figure 3. Circular space example.

As well as rectangular spaces, circular ones are also common forms, and these are used in rituals, particularly in modern Paganisms, and these are often formed by a circle of people. When it is a perfect circle there are two main emphasises, the centre of the circle, and the circle halfway between the centre and the circumference of bodies. In my experience the later tends to be stronger than the edge line, though the two can merge if the circle is 5 metres or less in diameter. The lines of emphasis in a circular space are stronger as there are less of them. If a piece of furniture such as an altar is placed at the edge of the circle or the space is an oval, it creates an axis of emphasis and another weaker axis at a right angle to it. If all four quarter points along the circumference are treated in a similar way with furniture or large objects, this is even more the case. However, it is obvious that the centre of the circle is the focus of the space.

Barker noticed that theatres-in-the-round (which were built to break down the division of the proscenium arch) caused problems for productions using the space. The actors standing at the focus start to feel uncomfortable quite quickly, and the audiences pick up on this, and they start to shuffle in their seats, and their attention drifts. So set designers began to break up the over powering focus of the circular space with sets that created other multiple foci across the set, thus making the space more useable. I have noticed that many circular ritual spaces also do not have anything at the centre (for example most prehistoric stone circles) the centre is such a draw it is actually very distracting. In my experience when the centre is used it is used sparingly, but the ‘halfway line’ between the centre and the edge is where most of the actions take place, generally in the form of stepping forward from the edge to move and speak, before returning to the centre. Even in rectangular spaces such as conventional theatre stages avoidance of the central point can be observed. Hence stand-up comedians want to make it easier for their audiences to enjoy their shows so they rarely use the centre, and move around the stage. The comedian wants to make it an effortless experience for the audience. However, the discomfort of using the central point of emphasis of a space for prolonged periods can be useful in some rituals such as vigils, for as Marshall (2002) observed any effortful behaviour whether in a ritual context or not creates a hardening of belief and belonging, so making it difficult can make it a more powerful experience. In the Liturgical mode of ritual (as defined by Grimes 1982) ‘waits upon power’ and so uses these points sparingly, however in the Magical mode of ritual it is all about wielding power, and those doing the magic stand at the foci of the magic circle to focus and wield the power.

Here are a couple of interesting ritual examples I experienced in 2003. At a Catholic wedding I attended in Penzance the priest left the principle axis intersection of the space of the conventionally laid out Catholic church and gave it over to the parents for them to bless the couple, rather than himself. He relinquished the space and the power, moving himself right over to the wall. At Anglican Christening I attended in the same year I was initially confused. I thought the proceedings shambolic, I was expecting something more formally in the liturgical mode. However, the font, and people were arranged very loosely with no regard to the structure of the building or anything else. During the ritual the priest was chatty, informal and scuttled off to get props (he even read out the stage directions for what he was required to do). The informal arrangements including the spatial ones, were taking the liturgy into the Celebratory mode of the seemingly ‘spontaneous’ (as Grimes would put it). This and other rituals I have experienced makes me think that the Celebratory mode has fewer spatial requirements than the other modes; power is shared between all so lines of emphasis in the space that would raise some above others are deliberately broken up. This example also illustrates that what is called liturgy (or any ritual script) can be done in Magical, Celebratory, Ceremonial or Liturgical mode as defined by Grimes. And I have frequently heard dissatisfaction with rituals in the fluid traditions of modern Paganism that are due to expectations of a ritual experience being performed in one mode, when what they get is another mode. The different modes of ritual are quite distinctively different experiences.

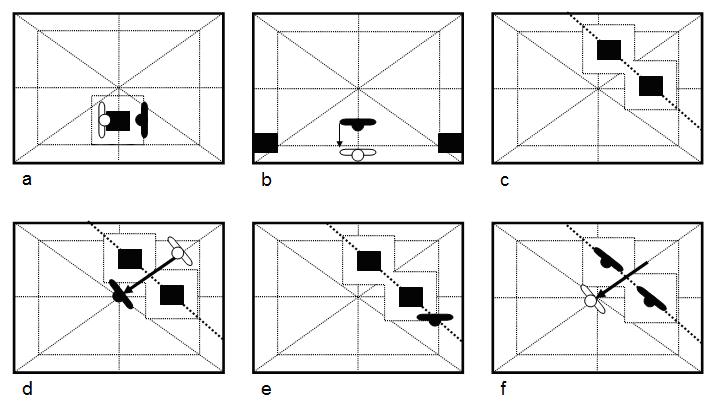

Figure 4. Thresholds in space examples

In example 4a a small table or altar is placed in the space. This creates a zone around it similar to the edge of the space (example 1b). And as with that example the black position is more emphasised than that of the white position as the black position is on the line of emphasis. The black position is separate from the table, and has equal emphasis in the space, whereas the white position merges with it, ‘becomes part of the furniture’, almost subordinate to it. The relationship between a monarch and the throne is an interesting example. Even though both positions are just as visible to the observers they feel very different. This obviously has implications for the use of altars within ritual; though which position is appropriate will depend. In example 4b two chairs or small tables are used to create a classic theatre proscenium arch, the line between the feet of each side of the arch is well known in the theatre as a strong threshold to cross. The black position is felt to be cut off in the ‘stage’ space, whereas the white position on the line between feels edgy, and being fully in the narrow strip that is in the same space as the audience feels more intimate (this is the area used mostly in pantomimes to directly converse with the audience). Theatres were redesigned in the 20th century to try and overcome the distancing separation of the proscenium arch.

In the next example 4c, the effect is similar to the proscenium arch of the previous, the two chairs are used to create a doorway or gateway, which has an even stronger threshold line than that of the wide proscenium arch. In 4d the effect of moving across this narrow focused threshold is magnified, and it is shaped by just how one passes through it. Stage sets are full of these gateways formed by furniture, and how actors pass between them communicates much about the characters they are playing. These gateways emphasise the liminal, the edgy, neither one thing nor the other status of the place between them, and crossing denotes a change of state. The position shown in example 4e has an even more uncomfortable position to stand than in the middle of the gateway. Whereas standing in the middle of the gateway feels like a point of decision, standing beside the gateway is being ‘sat on the fence’, and not committing to either side or to not making a choice. These are used sometimes within rituals, and are appropriate as many rituals are about changes of states, seasons or rites of passage. The transition effect can be emphasised even more in 4f if the two chairs are replaced by people in the two black positions who turn on the spot as white passes between them. The effect is different whether they end up facing in or facing out, it feels as if the white position is moving between inside and outside.

Conceptual Space: awareness and state of mind

We have looked at Bodily Space and Built Space these obviously overlap, but they have their roots in embodied cognition. Lakoff and Johnson have observed that the container is one of the primal metaphors underlying human embodied experience. The container metaphor is projected on to our bodies, the bodies of others, objects, groups, buildings and concepts. These different projections can overlay each other increasing the definition of each.

As many have pointed out (listed comprehensively in Harvey 2013: 83) the boundary line that defines a container from its surroundings, whether this be a cell of an organism or a cell that is a room, connects as much as it separates. All boundaries are permeable to something; sound, light, air (and as Harvey (2013) observed) food, sex and strangers. What is on both sides, touches the same boundary. Therefore the boundary is a place of tension between connection and separation. It is betwixt and between. It is relational. There is exchange across it; exchange of what is both desired and feared. Both communication and contamination. There is difference on each side, but there is never absolute isolation.

The container metaphor becomes most tangible in the solid form of buildings. Here how free or controlled relations across the boundaries are can be clearly seen. Markus (1993:13) described the raison d’être of a building is to interface Visitors and Inhabitants and to exclude Strangers. The Strangers are those excluded from the building, the Visitors are those permitted some access and the Inhabitants are the permanent occupant. However, the Inhabitants are mapped onto the social knowledge of the building and so they do not actually need to be physically present (Hillier and Hanson 1984: 146) Buildings and other spaces control interface and exclusion at their external and internal thresholds. Inside they are structured to shape interactions between Visitors and Inhabitants. Just think of comparing a high street bank to a visitor centre; each respectively emphasise and de-emphasis the distinction between the two groups.

The Inhabitants container coheres with part of the building container, and a space is provided for the Visitors containers to cohere. The Strangers are beyond the container, but means may be provided to enable them to take on the role of Visitor. The Visitors space is not as Included as the Inhabitants, nor is it as Excluded as that of the Strangers. So the space provided for Visitors has a fuzzy, betwixt and between, liminal quality to it, they neither totally belong, nor are they totally excluded. The Inhabitant-Visitor boundary is primarily one of transaction. The Visitor-Stranger boundary is one of exclusion.

When I applied Markus’s methodology to religious buildings (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012) I made a number of observations including:-

- The Inhabitants have little/no space at all in the building. There is an implied space that lies beyond from which the Inhabitants may come to visit or be available for interaction across the threshold. The Inhabitant-Visitor threshold is the focal point of the Visitors space and their actions in religious buildings.

- The permeability analysis shows that they have freedom of movement, it is their space, but defers to the Inhabitants who are partly in and partly beyond the building. Nearly all of the space is used by the Visitors. It is to meet their needs. It is the Visitors building as they support, use and maintain it, but to some extent they behave as if it isn’t. Neither fully public or fully private. There is a liminal fuzziness to their role, even more so than with Visitors to other types of building.

- Due to the majority of the space being Visitors’ space, the distance between the two thresholds, that of transaction with the Inhabitants, and that of exclusion from the Strangers includes most of the building, making most of the building an appropriately liminal place for ritual practice.

The Inhabitant-Visitor threshold can take a variety of physical forms, but it is often a counter or table, and in a ritual context often an altar. This is a practical form of boundary for physical and non-physical transactions between Inhabitants and Visitors. It provides somewhere to place objects, there is some visual or physical access across it, but there it also acts as a barrier. However, it also less obviously takes the form of statues, and invoked individuals.

For example in Whitehead’s (2013: 4-8) study of “Religious Statues and Personhood” with respect to the Glastonbury (UK) Goddess and the Virgin of Alcala (Spain), the devotees statues are both described and treated as representational images AND as powerful persons, with whom they make promise, strike deals and negotiate. This effect is aided by the images or statues actually react, reacting as part of the ritual performance as Pentcheva (2006: 640) observed with Byzantine icons the manner of worship causes candles to flicker and so the icons are seen to react. How they are related to by the devotees changes their status from inert matter to inherently powerful. The statues are liminal, they switch between states; they are not the deity, but they become the deity. They are the portal through which the divine arrives. When these liminal objects are placed at the liminal point in the space coherence between the two builds the liminal qualities of the statue. When they are removed from the shrines and processed outside Whitehead (2013: 141-3) observes that the boundaries between public and private are tested, the relations to it are put under strain. The Inhabitant is now not in their space but in the space for Strangers.

“When the statue is taken out of her shrine, the relationships that the people have with her are placed under a certain strain which indicates that the whole of this vernacular religiosity is fundamentally based on the statue being present in her shrine where she can physically be seen and/or accessed.” (Whitehead 2013: 143)

The statue is empowered by the space and defined by it, just as a king is more a king on the throne, than off it. For being not on the throne implies being without it or dethroned. A space helps define what something is by the coherence of the containers. Also the statue is a threshold, which as it is already in an unstable between state, so making it mobile makes it even more unstable, and perhaps too much for something used as a focal anchor point for community worship.

In Gabriel’s 2013 study “Playing God. Belief and Ritual in the Muttappan Cult in North Malabar” India, we have individuals in whom deity is invoked having a similar liminal status and being related to in similar ways by devotees. Literally “a moving idol” (Gabriel 2013: 5), spanning both human and divine (Gabriel 2013: 10), another liminal between state where this time a person is the temporary portal for the deity, as with the statues in Whitehead’s study. The actor in the invoked role is described by Hauser in another example of ritual theatre as “a vessel that embodies the divine (Hindi: pātr, literally: utensil, actor).” (Hauser 1973: 470). The difference in caste between worshiper and the invoked is seemingly ignored, high caste respects and bows to the low caste whilst they are invoked. Gabriel (2013: 5) noted that the greater the reversal in the roles for the invoked the more intense the experience. This was another added betwixt and between quality enhancing the liminality of the role. Even the performance of invoked person in the ritual itself is seen as an offering or sacrifice (Gabriel 2013: 10). So the acts of the invoked person are part of the threshold transaction, as well as the invoked person being that threshold.

The statue, image, or invoked individual has liminal quality, they are both treated as divine and non-divine. Their liminal quality is enhanced by being placed at the threshold of the Visitors space, which is a coherence of the boundary of the container which is the group, the container which is the built ritual space and the container which is the activity of the ritual itself.

The subtle interaction of spatial metaphor, the space within a building and the space around a person or object is difficult to express in words, but when these are brought together they can be strongly and deeply felt. How the different roles of Stranger, Visitor and Inhabitant interact I explore in more detail on the next webpage, ‘Thresholds of spaces’.

References

- Barker, Clive 1977 Theatre Games. A New Approach to Drama Training.Methuen.London.

- Briggs, Helen 2008 “Blind man navigates maze” on http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/7794783.stm last updated 22 December 2008.

- Gabriel, Theodore. 2013. Playing God. Belief and Ritual in the Muttappan Cult in North Malabar. Equinox. Sheffield.

- Harvey, Graham. 2013. Food, Sex and Strangers. Understanding Religion as Everyday Life. Acumen. Durham.

- Hauser, Beatrix. 2010 “Dramatic Changes? The Experience of Religious Play in the Megacity of Delhi.” pp393-413 in Michaels, Axel et al (ed) Ritual Dynamics and the Science of Religion. Vol II: Body, Performance, Agency and Experience. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Herbert, Wray 2008 “Arranging for Serenity. How physical space, thought and emotion intersect” in Scientific American Mind Volume 19 Number 4 pp80-81

- Irvine, Richard. Hanks, Nick. and Weddle, Candace. 2012. ‘Sacred Architecture: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives’ pp91-117 in Archaeology and Anthropology: Past Present and Future. ASA monograph series 2012. Berg. London.

- Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago.

- Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark. 1999. Philosophy in the flesh. Basic Books. New York.

- Markus, Thomas A. 1993. Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types. Routledge. London. New York.

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2006 “The Performative Icon” pp.631-655 in The Art Bulletin Review, Vol.88, No.4, Dec 2006

- Whitehead, Amy. 2013. Religious Statues and Personhood. Testing the Role of Materiality. London. Bloomsbury.

- Williams, Lawrence E. & Bargh, John A. 2008 “Keeping One’s Distance: The Influence of Spatial Distance Clues on Affect and Evaluation” in Psychological Science, March 2008 Vol.19, No.3

- Wiseman, Richard. 2012. Rip it up. London. Macmillian.