Permeability analysis was developed by Hillier and Hanson (The Social Logic of Space 1984) as a method for understanding how the space with in buildings is used by mapping the interconnectedness of spaces and the movement between them rather than looking at the architecture and the decoration. The space is what is the bodies inhabit, use and experience. The permeability map reveals the social organization and ideology projected on to the arrangement and connectivity of rooms. I developed this method with ideas from archaeology and performance to apply it to religious buildings and to more transient spaces created during rituals within larger rooms. My case studies were eight different faith buildings in Bristol, England; Anglican Christian, Baha’i, Buddhist, Druid, Hindu, Muslim, Reformed Jewish and Sikh. My study found a pattern to the use of space across these faiths that differed uniquely from non-religious buildings and which mirrored the ideas of Durkheim on rites of passage. A summary of the results were published in 2012, Irvine, Hanks and Weddle. ‘Sacred Architecture: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives.’ pp.91-118 in Archaeology and Anthropology: Past, Present and Future. ASA (Association of Social Anthropologists) monograph.

The following is an expanded version of the paper given at the EASR (European Association for the Study of Religion) 2012 conference at Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden. It includes extensive quotes from the Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012, and covers the following areas:-

- Internal adaptations to Permeability Analysis – Sikh Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Bristol, UK

- External adaptations to Permeability Analysis – Druid Ritual at Stanton Drew Stone Circles, near Bristol, UK

Why study the space

In general terms studying the space is a fruitful line of inquiry for many reasons:-

- Stable and accessible. Particularly when it has become architecture. Many [Turner (1987: 94), Bell (1997: 59) Merrifield (1987)] have observed that the practice of ritual is more stable and endures longer than the specific meanings attached to it.

- Part of the frame for ‘ritualising’ acts

- Construction or maintenance similar effect to ritual itself. As Marshall (2002: 369) puts it any “effortful behaviour” is of itself “likely to produce a quasi-religious hardening of belief and belonging”. So all of the background of the ritual itself the work of committees, organisation and arranging things contributes to the ritual process

- Social knowledge is mapped on to the organisation of the space (Hillier and Hanson 1984). More of this shortly

- Bodies in space are essential to the experience of ritual. Many [Owoc (2001), Bell 1997, Marshall 2002, Grimes 1982)] have argued that ritual is more than the merely social or cerebral. It is also physical. Bodies in space. The space affecting the body and also the body changing the space. In particular, this has been noted by Clive Barker (the drama theorist with whom I did a number of performance workshops about space) who shows that there is…..

- No such thing as an empty space. It is not an irrelevant, blank background. Space is dynamic

Personally I started to look at this area and use permeability analysis for mainly two reasons:-

Firstly, I noticed that the understanding of ritual among archaeologists of prehistory in Britain was lacking in some respects. Partly this was due to them largely being outsiders when it came to ritual practice. Sometimes ideas were borrowed from other disciplines without fully understanding them. Durkheim’s idea of the liminal, for example, (which I shall return to later in this paper). This transitional state is the central phase of rites of passage, and as I found through my research, is at the centre of ritual spaces. However, the betwixt and between state of liminality was only applied by Archaeologists at boundaries and edges. So there is a gap in the understanding of the ritual spaces.

Secondly, permeability analysis does not seem to have been applied to ritual buildings and spaces……

What a building / space is

Markus’ great study ‘Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types’ introduced me to permeability mapping. However, Markus studied the emergence of post-medieval modern buildings types but not new ritual building types such as Masonic Halls and Christian Non-Conformist chapels. I developed my approach by working on these building types as a pilot project. I then went on to apply it to the buildings of eight different faiths in Bristol. I noticed what appear to be unique qualities that make ritual buildings differ from (most) other buildings. Markus (1993:13) observed that the raison d’être of a building is to interface visitors and inhabitants and to exclude strangers. For any defined space has an inside and outside and a boundary. What or who, is in, is out, and is allowed to cross the threshold. In my case studies the inhabitants were mostly non-corporeal. “Of course, our understanding of access and movement in a sacred setting must consider more than the physical. Hillier and Hanson (1984, 146) state that “an inhabitant is, if not a permanent occupant of the cell [building/room], at least an individual whose social existence is mapped into the category of space within that cell: more an inhabitant of the social knowledge defined by the cell than of the cell itself.” In the work of mapping buildings used for religious purposes, it becomes apparent that the divine or other sacred presence within the space also needs to be considered an inhabitant.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 93)

Permeability Analysis

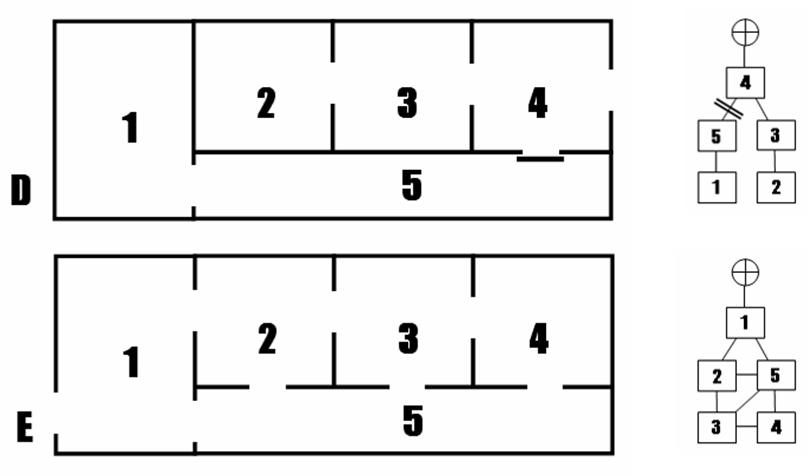

Permeability analysis was an idea developed by Hillier and Hanson in ‘The Social Logic of Space’ (1984) as a methodology for looking at the spaces within a building rather than the architecture of the building. Space and freedom of movement affects people. Permeability analysis shows how strangers, visitors and inhabitants interactions are controlled/expressed by the spaces. This reveals aspects of the social organisation and ideology projected on to the arrangement and the connectivity of rooms. Marcus (1993) summarises Hillier and Hanson’s work very well. Those who have a good spatial sense such as those with dyslexia will find this easy to understand, but for those who do not have that advantage here is a simple example. “Alterations in the positions of doorways can radically change the experience of visiting a building. Building E has rings of freedom of movement, whereas D has separate branches, one with a controlled door. Both buildings have three layers of depth.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 92) Changing the position of the doors can also change the distance from the outside and thus increase the number of layers of rooms; the ‘depth’ of the buildings permeability. Doorways are the point that controls the access.

Figure 1. Two simple building plans and corresponding permeability plans

Good examples of the use of this technique include:-

- Marcus (1993) who applied it to a large range of building types, and he also added the aspect of inter-visibility between rooms, such as in prisons.

- West (1999) who applied it to the country house setting with its two distinct groups of inhabitants, illustrating how different groups can have different degrees of freedom of movement within the same building.

- Gould (1999) who shows how quickly the method can be applied that it can be used as part of a rapid photographic survey to record buildings prior to demolition. This is one of the techniques main virtues, there is no need for measuring and accurately planning the space. A sketch plan from a brief visit is all that is required, one is recording the spaces and the connections between them, and only noting the architectural detail. So it can be done discretely one just needs a notebook, and perhaps a camera, to capture the permeability plan.

Internal adaptations to Permeability Analysis – Sikh Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Bristol, UK

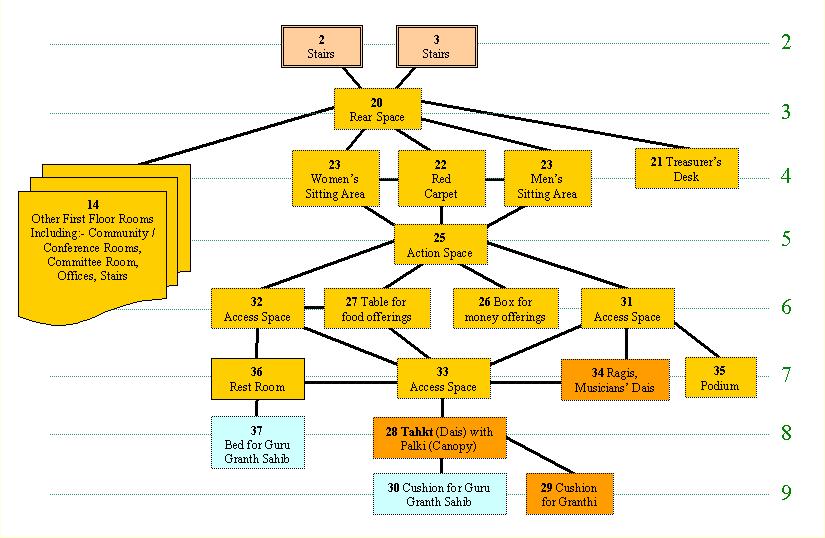

I made some adaptations and additions to this technique to record more about the buildings I was studying and to make the analysis more qualitative rather than the more quantitative approach of Hillier and Hanson:-

- Replacing dots to represent rooms/spaces on the permeability diagram, with text boxes. This enabled me to add a name to the room numbers.

- Colour coding. This was mainly to enable me to distinguish different types of spaces, such as by the types of activity carried out there or by what floors of the building they were on. I interviewed a user of each of the buildings about what activities were carried out where in the space either while visiting the space or while looking at a sketch plan of the space.

- Treating spaces within rooms the same as rooms. Obviously the spaces are inter-visible with each other within the room unlike the situation between most rooms, but there are ‘walls’ and ‘doorways’ between these spaces created by furniture, by the people in the space and by the proximity to objects. For example, the block of seating in a lecture room can be defined as a space and that the access corridors as another. We sense that the space next to a lectern at a conference is a different space from that on the rest of the stage. We also sense locations not marked by objects but defined or respected by the movements and actions of people. For example a location from which a series of individuals take turn to speak. Clive Barker explored these spaces within spaces in great depth in theatre workshops that I attended as an undergraduate (for more details on these workshops see the Bodies and minds in space page), which he wrote about in his book on training actors (1977). (In addition following the movements, objects and directions of speech can reveal much as they play their part in expressing interactions with others and the ritual focus.) However, these ‘spaces’ are fluid as both can be re-located during the ritual or ignored by people, and I admit that there is some subjectivity with defining their extent and number.

Figure 2. Permeability plan of main hall of Sikh Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Bristol, UK

Figure 3. Sketch plan of main hall of Sikh Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Bristol, UK

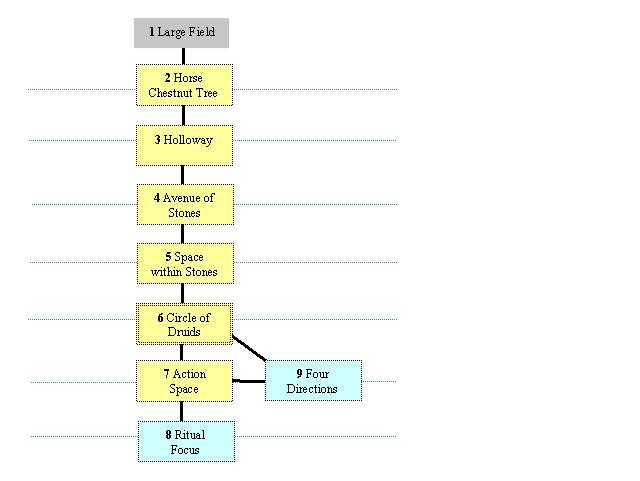

External adaptations to Permeability Analysis – Druid Ritual at Stanton Drew Stone Circles, near Bristol, UK

I applied this technique to spaces created within larger rooms. And it can also be applied to temporary spaces created outside, but here there are slightly different issues.

The Druid group I studied are using a prehistoric stone circle. The stones of even the smallest circle are too wide and people gather within them so the stones do not define the main ritual space, but act as a permeable outer boundary. Those who do not wish to participate, and random visitors to this prehistoric site, watch from the stones, but see/hear very little as the cloaked people close enough to hold hands make almost a solid wall. The bodies of the main circle are both a barrier and a space. It is semi-permeable, people duck in and duck out, but it is mostly respected, as is entering the circle via the processional avenue of stones.

The procession is lead from a tree which is used as the gathering point providing some shelter in the open field. Then the route is defined by an earthwork hollow and then an avenue of stones. The procession helps to both gather people together to commence the ritual, but also they move as a group and so it also help to create a sense of belonging to the group. It also provides a sense of spatial separation despite the fact the site is a wide open field.

The main ritual space and the spaces within it are totally created by objects, actions and bodies. The four cardinal directions on the edge of the circle are marked by bearers of staffs and objects at their feet. They also turn outward and lead others in facing this direction. The centre is also marked with a few objects in the grass, but it is only used sparingly for key actions in the ritual. This minimal use of the centre is consistent with Barker’s observations in theatre. Also consistent with Barker, most of the actions taken by those who step forward from the group take place halfway between the centre and the edge, thus creating another space.

Figure 4. Permeability plan of Druid Ritual at Stanton Drew Stone Circles, near Bristol, UK

Figure 5. Sketch plan of the eastern circle at Stanton Drew Stone Circles, near Bristol, UK

This particular ritual space example is simple due to a number of limitations. This Druid group do not own the stone circle, are unable to permanently alter it and there is little time to set-up anything much before the ritual begins. As was an open ritual, many of the participants are not trained in Druidry and so do not know where to stand and what to do and without obvious architecture to guide them it is necessary to keep arrangements simple.

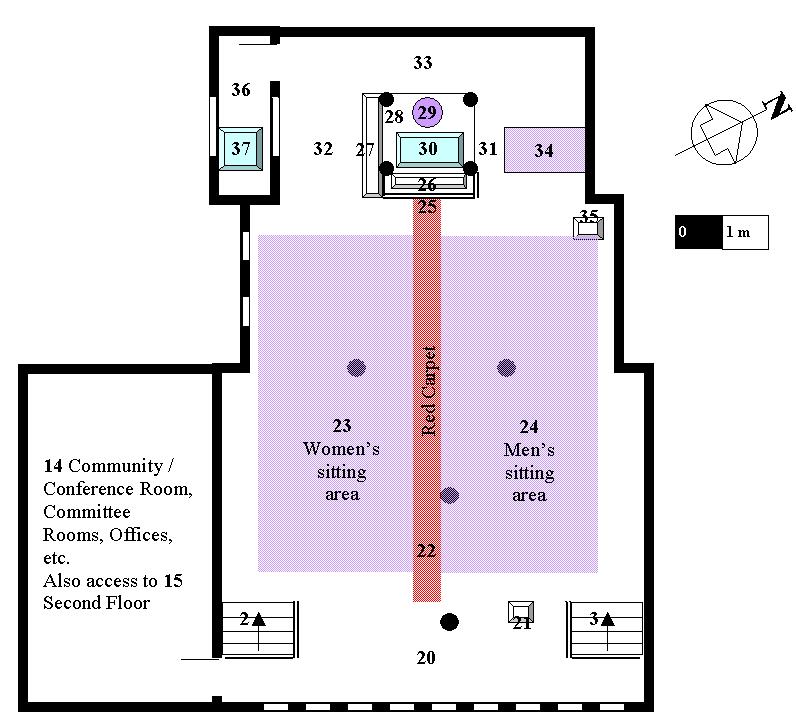

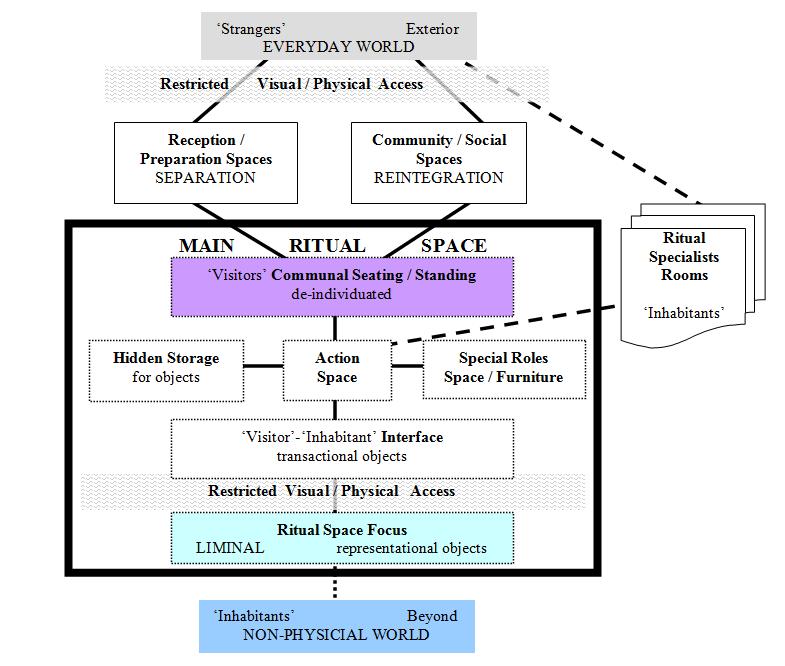

Proposed Model for ‘Liturgical’ Space

“When this method of permeability mapping, adapted to the purposes of sacred space, was applied to the eight buildings, it immediately became apparent that each had spaces that corresponded to the three phases of ritual activity as refined by Victor Turner (1969) from Van Gennep’s famous work on rites of passage: separation (lobby/reception room), transition/liminal (main ritual room), and incorporation/reaggregation (community/socializing room). Though for some buildings the community spaces are not present in that actual building, they are instead represented in other buildings used after the main ritual activity. These features and other common elements noticed by Hanks are drawn here as a simplified permeability map. The reception spaces help to facilitate separation of sacred and profane in two ways. Here visitors prepare themselves before entering the main ritual space: removing shoes, changing clothing, washing, and putting aside objects/materials that are not permitted. Thus they distance themselves from the world and thoughts of it by changing from their everyday appearance and leaving worldly things here. The reception space also acts as a means of separation from the outside world by creating physical distance and restricting both visual and physical access. We will explore this need to exclude strangers later in this paper.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 93)

“The other connection to the exterior world is provided by the community spaces. These aid the visitor in the incorporation of the ritual experience into their lives, prior to returning into the exterior world. These spaces often provide literature and objects for visitors to take home to carry the beliefs and practices beyond the sacred space and into other spaces. Here the sense of group belonging is increased by sharing food and socializing, returning to more physical and worldly activities. They are also the spaces used outside of times of rituals for social and educational events that complement or support the visitors’ belief and belonging , which Marshall (2002), building on Durkheim’s work in Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1915), has described as the primary aims of ritual. These social and educational spaces that are more connected with the world are a place where strangers are most likely to appear, and they often require separate entrances to avoid passing through the main ritual space. In the Sikh, Hindu, and Baha’i examples, the reception and community spaces were located on the first (ground) floor, with the main ritual space removed to the second floor.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 94)

Figure 6. Proposed Model for ‘Liturgical’ Space (Irvine, Hanks, Weddle, 2012)

“The main ritual spaces studied have the majority of their area devoted to visitor seating or standing. This creates an emphasis on communality. Participants gather together in large groups facing the same direction, toward the focus of the ritual space; indeed, in some cases (as in the Sikh Gurdwara), there is even a prohibition on turning your back on this space. Being together en masse in communal seating allows for synchronizing of movement and voice (Hillier and Hanson 1984, 191); as Marshall (2002) would put it, de-individuating and co-presencing the visitors to increase the sense of belonging. Between the visitors’ communal seating and the focus of the ritual space is a space where actions can be directed toward that focus. Significance is given to the actions by their close proximity to the ritual focus, and their high visibility in the area toward which all are looking. It is the point of closest approach for visitors to the ritual space focus. The ritual space focus is that point to which the visitors look, move, voice, and make actions. Also, as this space for actions is only occasionally used, it adds a sense of distance between the ritual space focus and the visitors, as well as heightening the significance of actions carried out there. Some people, of course, may have a temporary or permanent role separate from the group. This role may be indicated by a piece of furniture, such as a lectern or platform.

The physical objects at the ritual focus have two roles: “transactional” and “representational.” Representational objects, according to Scarry (1985, 314), are intended to have a psychological effect, be it to act as a reminder or to inspire with awe and mystery. They are not considered to “be” what they represent. They point to something beyond or are accessed by something beyond. Then there are the offerings, of artwork, food, or money (but also nonmaterial offerings such as praise), which Grimes (1982, 94) observes are primarily transactional and made toward the ritual space focus from which the visitors seek to gain benefits. There may be adjacent or combined locations for the transactional and representational objects, for example, a table before an image. Though transactional objects were present in all eight cases, the representational objects were not. The ritual space focus is a material aid to the attentional focusing behavior that, according to Marshall(2002, 363), is an essential part of ritual’s objective of removing attention from the self and creating immersion in the group. However, the need to focus attention is more important than the subject of that attention (Marshall 2002, 361); hence, the ritual space focus can be physically empty in some cases, particularly when the visitors are in a circle facing the center, which is strongly defined by the obvious geometry. The Baha’is, for example, had only a small table at the focus of their circular space.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 95)

“It has been noted by Renfrew and Bahn (2000, 406), among others, that ritual has both a “conspicuous public display” element, with the highest concentration of ornamentation being at the ritual space focus, and a “hidden mystery element,” or, as Nash (1997) described it, “restricted visual access.” Both of these seemingly “contradictory observations can apply to the ritual space focus in the same building. The role of ornamentation in aiding attention focus is obvious, but the role of hiding is less obvious. In all of the eight examples Hanks studied, the foci spend at least part of their time hidden by curtains or doors, hidden from view as a result of actions such as bowing or closing the eyes, or “hidden” by virtue of being an empty space. The decoration itself may be used to obscure or hide the object of the focus. Why? Hanks’s research leads him to suggest that it adds to the liminal nature of the ritual space focus by rendering it both seen and unseen.

For many years, through his work in the theater, Barker (1977, 135–55) has tested the subtle qualities of space and the effects that these have on the mind and body. One of his observations is that the strong focus of a space, created by the architecture, the furniture, and the actors, is both uncomfortable to stand in and uncomfortable to watch for very long, and that both audience and actors become physically restless. The strongest examples described by Barker were the theaters-in-the-round built in the 1960s, in which the center point was not used and was in fact deliberately weakened by set design, because the strong focal emphasis of the architecture created great difficulties. It is worth noting that two circular examples of space in Hanks’s study, used by Druids and Baha’is, made little or no use of the center of the space. Such cases may suggest that, for physical reasons, the visitors to the space need some degree of rest from the strain of the ritual space focus. Grimes (1982, 43–44) notes that the liturgical mode of ritual “waits upon power” rather than wields it; in such a context it would be appropriate to avoid physically occupying or allowing prolonged observation of the point where the spatial/attentional power is at its strongest. Unlike other building types examined by Markus (1993), in the ritual spaces studied by Hanks the point of interface between the visitors and the inhabitants seems to occur at the deepest point of the building. Indeed, the way that the ritual space is used directly implies a focus beyond the space within the building. For Muslims, the focus points toward Mecca; in the case of the Sikh Gurdwara, it reaches toward the Golden Temple. For Hindus, the statues are “considered to be access routes through which spirits could enter and leave the world” (Mann 1993, 95). The ritual space implies a permeability beyond the limits of the building, toward a greater reality that worshippers might someday gain access to. There is therefore a perceived invisible extension to the structure of the building that leads elsewhere. The building is permeable by the divine through the gateway of the ritual focus. One could say it is half a building, physically incomplete just as the process of liturgical “waiting” is incomplete. This would seem to be a defining feature of liturgical ritual buildings.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 96)

“Another part of a building’s function is the exclusion of strangers, which plays a particular role in preventing disruption of liturgical ritual. None of the examples in Hanks’s study has direct access from the outside to the main ritual space. Access is controlled by doors and bells, and is observed by cameras and windows. This increases the sense of separation from the ordinary world, in the same way that the ritual focus is also at the opposite end and at the deepest point in the permeability. More generally, there is “restricted visual access” from the outside, as has also been observed by Nash (1997) at prehistoric sites. This discourages strangers from visiting. One cannot see in, and the activity within is not on display; this is in contrast to visitor centers with their large windows and wide-open reception areas.

It is significant that the eight buildings Hanks studied have little or no signage or publicity to encourage visiting by strangers. Access is limited to formal arrangements, such as school trips and Bristol Interfaith events, or as part of the national Open Doors Day scheme. Though theologically most religions take the position that they are open to all, in fact it appears that liturgical ritual space works to exclude strangers. Access is only on terms that will help preserve what occurs therein. The attentional focusing of the liturgical ritual is needed to draw attention away from the self, reducing self-awareness and any sense of separation from the group (Marshall 2002, 363). Outsiders may conflict with the sense of belonging engendered in ritual, and it may also be suggested that strangers make participants self-conscious—the sense of being observed by others may therefore reduce the attentional focus of the ritual. It is with this in mind that particular etiquette is advised for visitors, managing the nature and extent of their visibility.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 97)

“In analyzing these processes, it is important to recognize that sacred spaces are subject to change and are themselves the products of transformation of pre-existing spaces. ….the buildings studied by Hanks…..have all been modified to varying degrees by the communities that use them, and this work on the buildings does not end; there are embellishments or extensions, ongoing repairs, and cleaning. It may be suggested that this process contributes to the aims of ritual. This “effortful behavior” is of itself “likely to produce a quasi-religious hardening of the initial or associated beliefs” (Marshall 2002, 369). The building itself, and its continuing adaptation, is part of the ritual process, not simply a frame for ritual activity or a shelter to house it.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 102)

‘Liturgical’ Ritual Mode Case Studies

The case studies which I looked I did do not have time to cover here, but the detailed notes and analysis will be added to this website on the case studies page. Only ‘Liturgical’ model has been published, rather than the details of the case studies that were the basis of the model. However, this model is only based on eight detailed case studies of different religions in Bristol, UK, in the 21st century.

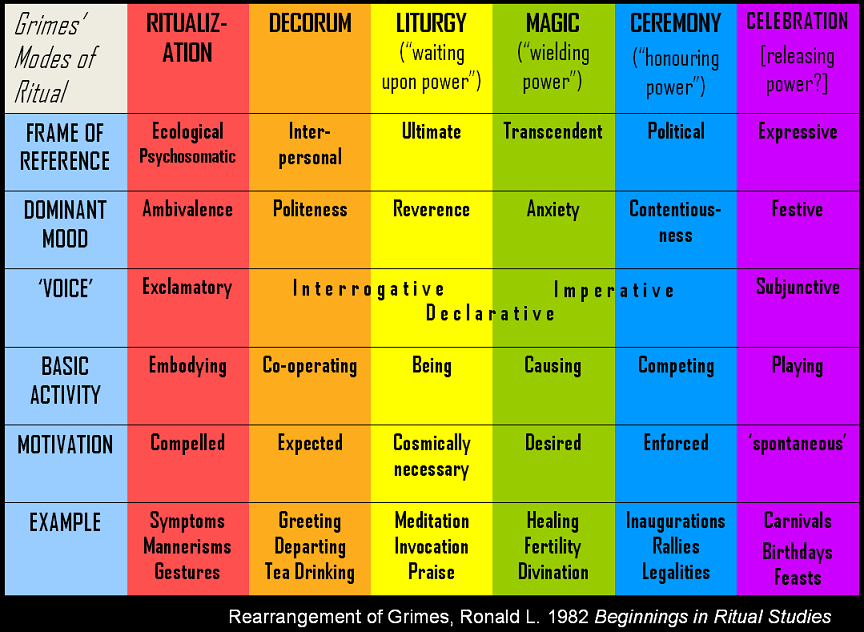

Figure 7. Rearrangement of Modes of Ritual table (Grimes 1982). The axis have been reversed and comments on power from Grimes have been added, excepting that on Celebration, which is my own suggestion.

Above is Grimes diagram of the modes of ritual, which is the best description of the full range of ritual practice. All of the eight examples I looked at were in the liturgical mode (with a possible exception of the Druids). But what are the spatial features of other modes? Or do they have none at all? And then what are the spatial requirements for processional rituals such as the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance? Does this apply when the religion/beliefs are that of the majority in the area? All my cases were minorities in a general population of non-believers. Is the Stranger-Visitor dynamic, and the need to restrict physical and visual access from the outside weaker in these cases? Will the fact that much of the space is defined by action and not by any material left, make this approach usable in archaeology? Does this apply to other periods of time?

I have some provisional ideas but am currently reading wider before embarking on some other fieldwork, but as I am not part of academic institution further research will be both slower and more difficult for me. I am hoping that others will use this technique so I have more case studies to expand into other modes of ritual. But I recommend this technique to you as an alternative approach to add to your research tools to get a fresh perspective on ritual space, that is quick to use in the field and flexible to different circumstances, but allows for diverse situations to be compared. “Permeability mapping….[is]…… a flexible and easily applicable method to use as part of the ethnographic process, aiding both specific analysis and cross-cultural comparison. It gets below the surface details of the decoration and iconography and becomes a map of social knowledge, revealing restrictions on the movement of the users of the building, and so the users’ hierarchies and exclusions. It makes vital interactions of people and space tangible and so can deepen our understanding of the ritual process. Yet an analysis of such processes also requires an awareness of the experience of ritual, including its sensory aspects, and it is here that auto-ethnographic methods are of benefit in helping us to grasp the intangible qualities of space that may not be visible in the material record.” (Irvine, Hanks and Weddle 2012: 112)

If you do use the technique I have described here I would dearly like to see your permeability plans for the benefit of my own research, and I am happy to help with any questions you may have about applying the technique. But since writing the 2012 book chapter my ideas have developed further on webpages ‘Bodies and Minds in space’ (2014) and the ‘Thresholds of spaces’ (2013).

References

- Barker, Clive 1977 Theatre Games. A New Approach to Drama Training.London:Methuen

- Bell, Catherine 1997 Ritual Perspectives and Dimensions.New York and Oxford:Oxford University Press

- Durkheim, Emile 1995 [1912] The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Karen E. Fields.New York: Free Press.

- Gould, Shane 1999 “Planning, development and social archaeology.” in The familiar past? Archaeologies of later historical Britain, ed. S. Tarlow and S. West, 140-54.London: Routledge

- Grimes, Ronald L. 1982 Beginnings in Ritual Studies Lanham & London: United Press of America

- Hillier, B. and Hanson, J. 1984 The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge

- Irvine, Richard. Hanks, Nick. and Weddle, Candace. 2012 ‘Sacred Architecture: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives’ in Archaeology and Anthropology: Past Present and Future ASA monograph series 2012

- Markus, Thomas A. 1993 Buildings & Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types. London ; New York: Routledge

- Marshall, Douglas A. 2002 ‘Behavior, Belonging and Belief: A Theory of Ritual Practice’ in Sociological Theory 20-:3 November 2002 pp.360-380

- Merrifield, Ralph 1987 The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic. London: B. T. Batsford

- Nash, George (ed) 1997 The Semiotics of Landscape: The Archaeology of the Mind. Oxford: BAR International Series 661.

- Owoc, Mary Anne 2001 ‘Bronze Age Cosmologies: The Construction of Time and Space in South-Western Funerary/Ritual Monuments’ In Smith, A. T. & Brookes A. (eds) 2001 Holy Ground: Theoretical Issues Relating to the Landscape and Material Culture of Ritual Space BAR International Series 956 pp.27-38 Oxford: Archaeopress

- Renfrew, C. and Bahn, E. 2000 Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, 3rd edition. London: Thames and Hudson

- Scarry, Elaine 1985 The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Turner, Victor 1967 The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

- West, Susie 1999. “Social space and the English country house.” in The familiar past? Archaeologies of later historical Britain, ed. S. Tarlow and S. West, 140-54. London: Routledge