Stanton Drew Stone Circles in the village of the same name in North Somerset, UK, a rarely visited or investigated site. This is surprising as it is second largest prehistoric stone circle in Britain after the World Heritage Site of Avebury. It is also a similar complex, with three circles, two avenues and a cove.

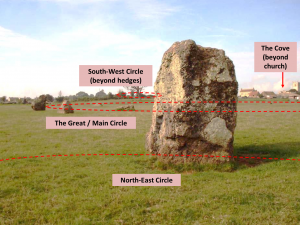

View looking south-west

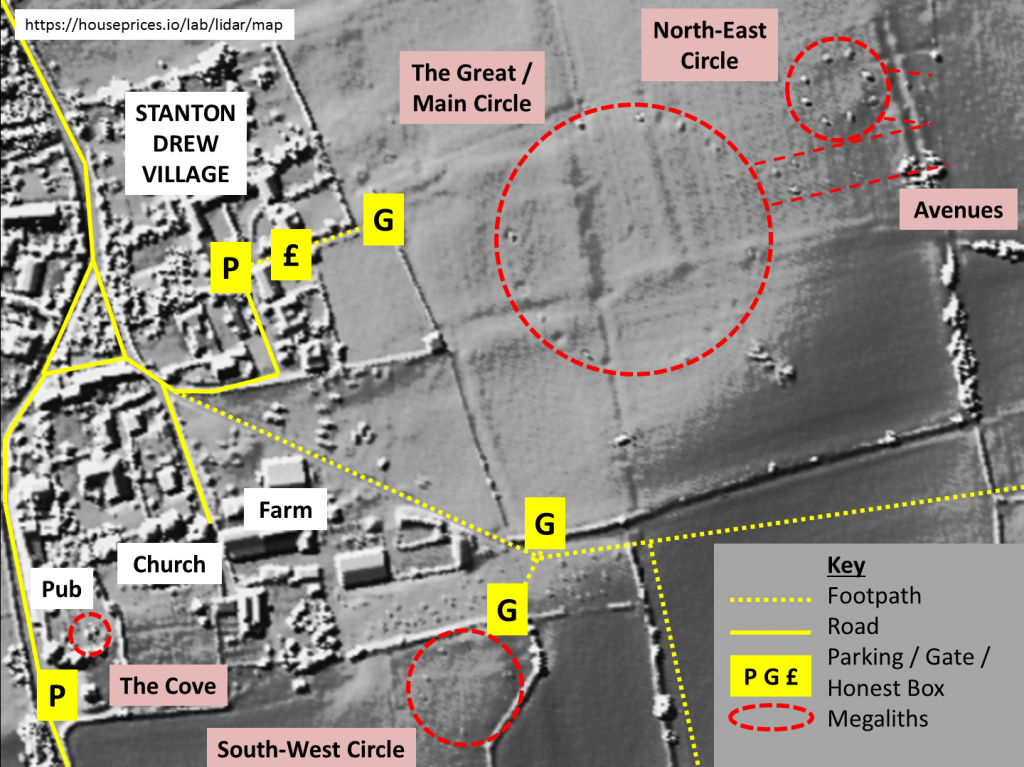

The lack of attention is partly due to the lack of promotion and on site facilities. There is no visitor centre or shop, and parking for only a few cars. There is an honesty box by the farm gate and a few interpretation panels are due to go up in 2018. The stones are in the care of English Heritage Trust, but the land is owned by a farmer. However, one part of the site is not in a farm field, and that is the cove, which is in the garden of the Druid’s Arms pub.

Archaeologists have largely ignored Stanton Drew as well. The lack of any burial mounds in the area (which is highly unusual for this kind of site) has mean’t that there has been nothing to draw anyone to excavate. So there is no accurate dating or sequencing for the site. All the work has been done above ground by surveying, some fieldwalking in adjacent ploughed fields but it is through geo-physical surveys that the complexity of the site has been revealed.

The page is based on a dayschool I prepared for the University of Bristol. It is a compilation of what is known about the site, but is not an area of original primary research by me. However, due to the popularity of the Stanton Drew and the current absence of a guidebook I have made this material available here.

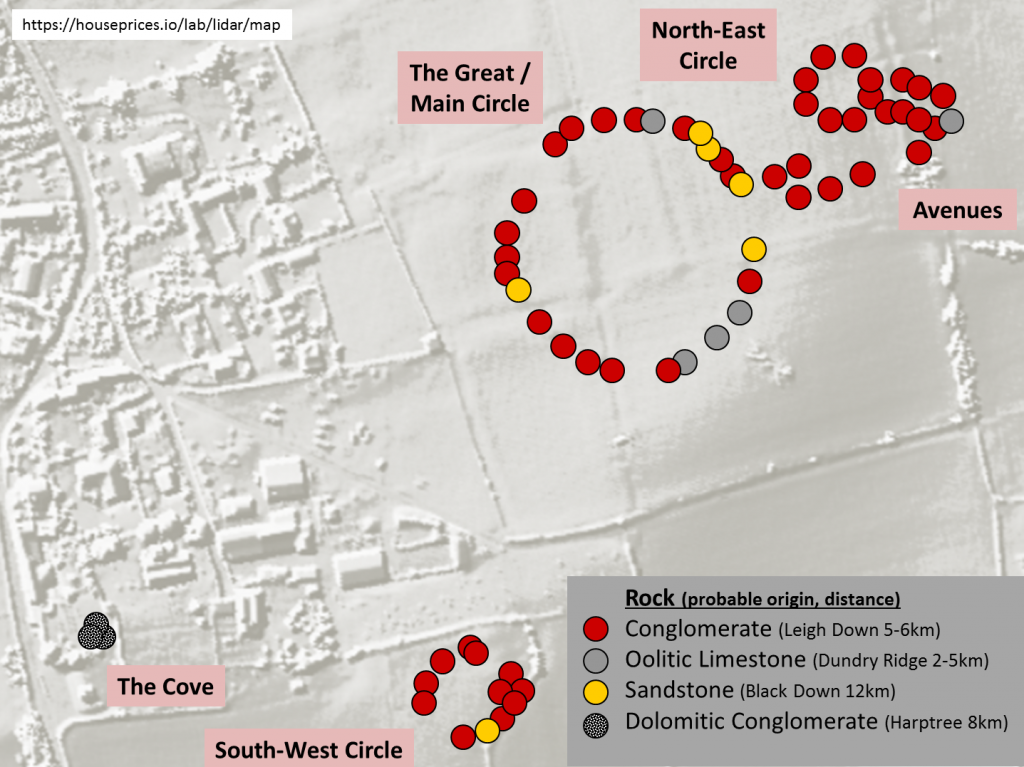

General plan on site.

Northern Somerset in the Neolithic and Bronze Age

They do things differently here. The prehistoric monuments of the Mendip Hills and the hills to the north towards Bristol are not exactly the same as Wessex (Stonehenge and Avebury), the Cotswolds, Cranbourne Chase or the Somerset Levels. Stanton Drew has all the elements of Avebury but arranged in a very different combination. Jodie Lewis (2005) has heavily researched this understudied area and its distinctive style.

Like elsewhere in the Early Neolithic there are a long barrows for performing public rituals with the bones of the dead. Unusually, there are no known middle Neolithic monuments, such as causewayed enclosure and cursus. In the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, like elsewhere, there is a separation of monuments for public use and burials, with henges, stone/timber circles and round barrows.

Stanton Drew had a ‘rival in Northern Somerset. Priddy Circles are four earthen rings arranged North-South in a landscape of late barrows and natural swallet holes into which offerings were sometimes placed. (There is no public access.) The banks were within the ditches and were held in place by approximately 1280 posts in total. The closest parallels to Priddy Circles are in Scotland. It is radio carbon dated to 2862-2400 BC, but with no date for Stanton Drew the relationship between the two remains unclear. However there are shared traits, the main timber circle of Stanton Drew does seem to have an entrance aligned to the North, and there are ‘fours’ in some of the structures.

Stanton Drew : Above Ground

These stones have a good share of folklore. There is a tale of a baker trying to count all the stones, which like many megalithic sites is said to be impossible, by placing loaves on each stone. Another tale says that the stones go down to the river to drink, which is also said of some other stones, but here there are two avenues of stones that actually head towards the nearby River Chew and end at the edge of the flood plain. Stonehenge as an earthwork avenue that leads to a river. This would likely have been the an approach to the site. Today one approaches from the opposite direction.

The earliest recorded name for the site is ‘The Wedding’ recorded in 1664 by antiquarian John Aubrey. Due to a high crop growing around the stones and hedges dividing the site he was unable to do an accurate survey. The story of the wedding party being turned into stone for partying overnight and on to the sabbath combines elements of two folk tales associated with megalithic sites.

The Cove

Firstly, there is the British and Irish ‘Merry Maidens’, a ring of dancers with a nearby fiddler or piper who were punished for dancing on a Sunday by being condemned to dance forever. The stones are either their bones, or they were turned to stone as a release from the torment.

Secondly, there is (mostly) French and Breton ‘Marriage of Stone’. A wedding party is turned to stone for disrespecting the priest, or Holy Sacrament or a passing funeral or procession.

The stones arrangement today expresses the story very well. The three stones in the pub garden by the church are the bride and groom (or cook), with the fallen stone between them the drunken parson. The main circle was the dancing revelers and the north-east circle the musicians.

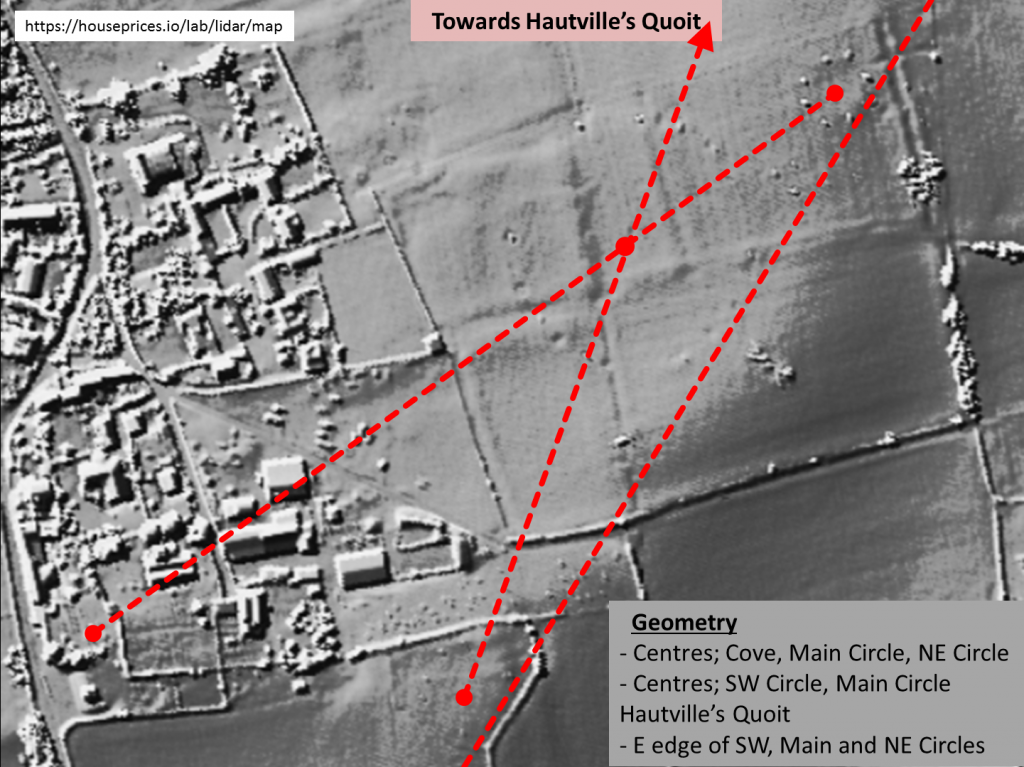

Aubrey also records the tradition that the outlying stone ‘Hautville’s Quoit’ (now hidden in a hedge) as having been thrown by a medieval local person of great strength, Sir John de Hautville. There is an effigy incorrectly identified as him in the parish church of Chew Magna.

William Stukeley was the next antiquarian to visit in July 1723, and he was the first to note the parallels with Avebury. The incompleteness of the site and the hedges separating the parts for it lead him to make a few wrong guesses. However, his companion John Strachey thrust a sword in to the ground and found a number of buried stones.

John Wood in 1740 is the first to accurately record the geometry of the site. He went on to use the size of the main circle as the basis for the Circus he built in Bath in 1754-8.

Geometry

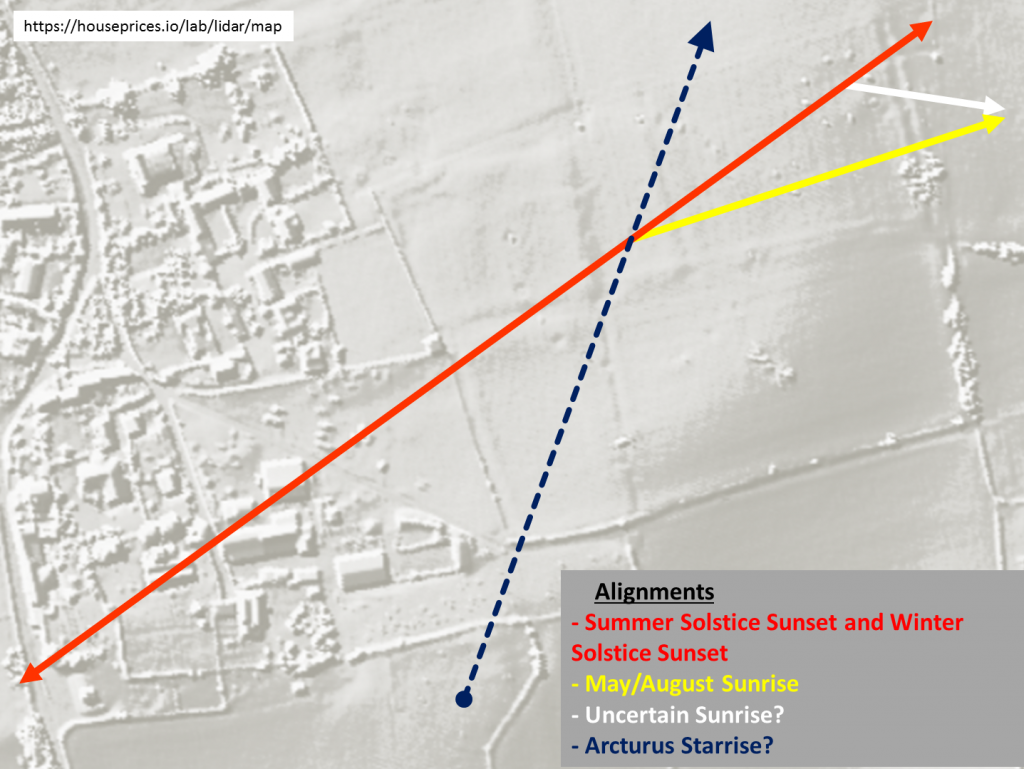

Then nothing much happens for over a century until Morrow (1898) and Locker (1909) look for the astronomical alignments. This proved to be tricky with mining having affected the skyline to the East, and the very broad width of the avenues. The North-West circle’s avenue aligns just south of east and today points at a former coal mine on the horizon. The main circle’s avenue would point to a May/August sunrise. The line that runs through the centre of these two circles and the cove is the same as the main alignment for Stonehenge, with the Winter Solstice sunset to the south-west, and the Summer Solstice sunrise in the opposite direction to the north-east. Though due to the high hills beyond one can only really look along it towards the south-west.

Alignments

Jodie Lewis (2005) identified the probable sources of the stone used. These came from four locations between 2.5km to 12km distant. The stones seem to have been left in their natural shape. There could have been all sorts of reason for the choice; spiritual, practical, aesthetic or cultural. By far the majority of the stones are a distinctive red conglomerate with small cavities filled with crystals.

Geology

Stanton Drew : Below Ground

The status of Stanton Drew Stone Circles was boosted enormously by the geo-physical surveys (Resistivity, Magnetometry and Ground Penetrating Radar) carried out in 1997, 2009 and 2017. All of this techniques measure subtle differences in the soil and reveal features that are easily lost if fires are lit on the site or the soil is disturbed.

The major discovery was in the main circle of the largest timber structure in Prehistoric Europe. Here there was the faint trace of a lost 7m wide ditch. It had a bank on both sides and a gap much wider than the stone avenue. More importantly however are the faint traces of nine rings of pits which probably held posts. The ring of stones stand between the pits and the ditch. The ditch, pits and stones, though all perfect circles, they do not share the same centre. This suggests they were built at different times, and they may not have all been present at the same time. As does the fact that a sight gap in the pit rings that runs towards the centre is orientated just off due North where there is no gap in the ditch. The probable sequence was pit/timber circles, the henge ditch and banks and then the stone circles and avenues.

If the pits held timbers they could have been up to 1.4m in diameter and were about 2.5m apart. With the multiple rings there would have been a stroboscopic effect with the sunlight as one moved between them. If the pits did not hold timbers, they may have been used for offerings like the Aubrey holes at Stonehenge. The posts would not have been a building as there is no eaves drip for the roof, and the central timbers would have needed to be 75m tall. This stone circle has many missing stones, some of the fallen stones can be seen sunk into the ground.

North-East Circle from South-West.

The North-East circle has four very large pits at the centre, aligned with the eight stones, with the gaps pointing to the four points of the compass. There were two smaller points linking the central two to the avenue, though it heads off in a slightly off direction to join the end of the main circle’s avenue. This is the most complete circle, and has the most massive stones.

The South-West circle combines features of the other two circles. Like the North-East circle it has four pits, and two towards what may have been the entrance. Like the main circle it has an enclosing ditch, and has rings of pits. These are also circular without a shared common centre like the main circle. Unlike the other circles it is on a natural rise in the ground affording views to more distant hills. The twelve stones of this circle are much smaller than the others; damaged, fallen and displaced.

References

David et al (2003) ‘A rival to Stonehenge? Geophysical survey at Stanton Drew, England.’ Antiquity Vol.78 Number: 300 pp.341-358.

Grinsell, L. V. (1994) Megalithic Monuments of Stanton Drew.

Lewis, J. (2005) Monuments, Rituals and Regionality: The Neolithic of Northern Somerset. BAR Series 401

Linford, N. Linford, P. Payne, A. & Greaney, S. (2017) Stanton Drew Stone Circles and Avenues, Stanton Drew, Bath and North-East Somerset. Report on Geophysical Survey.

Lockyer, N (1909) Stonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments Astronomically Considered. Macmillian. London.

Mowl, T. & Earnshaw B. (1999) John Wood: Architect of Obsession.

Oswin, J. Richards, J. & Sermon, R. (2009) Geophysical Survey at Stanton Drew, July 2009 Bath and Camerton Archaeological Society